If you haven’t read the first parts of this blog series about my adventure on “America’s Got Talent,” they’re here: Part 2

To recap the story: I was invited to compete on “America’s Got Talent” last March in Seattle, played James Brown’s “I Feel Good,” and was buzzed (rejected) with lightning speed. The show aired a few days ago.

So, yesterday a friend sent me the thread of a blog forum about my AGT performance that read: “Yes, it’s important for a professional musician to be flexible, but also to know where to draw the line so that one’s dignity is not compromised. For example, singing and playing James Brown’s “I Feel Good” on a national televised talent show may actually make you feel not so good afterward…”

Hmm… well … in fact, I felt elated afterwards. And my dignity … I’d compromise it any time to get at the truth. But I probably need to put this all into context, so first off, here are the 3 things that wove the backdrop for that moment:

1. Years ago I was signed to a record label, GRP, that had a specific ‘sound.’ For three years we struggled, them trying to make my music sound more “GRP” and me trying to sound like myself. When I looked back years later, I often thought, “If I did that again, I’d put myself utterly in their hands, just to see where the ride would take me.”

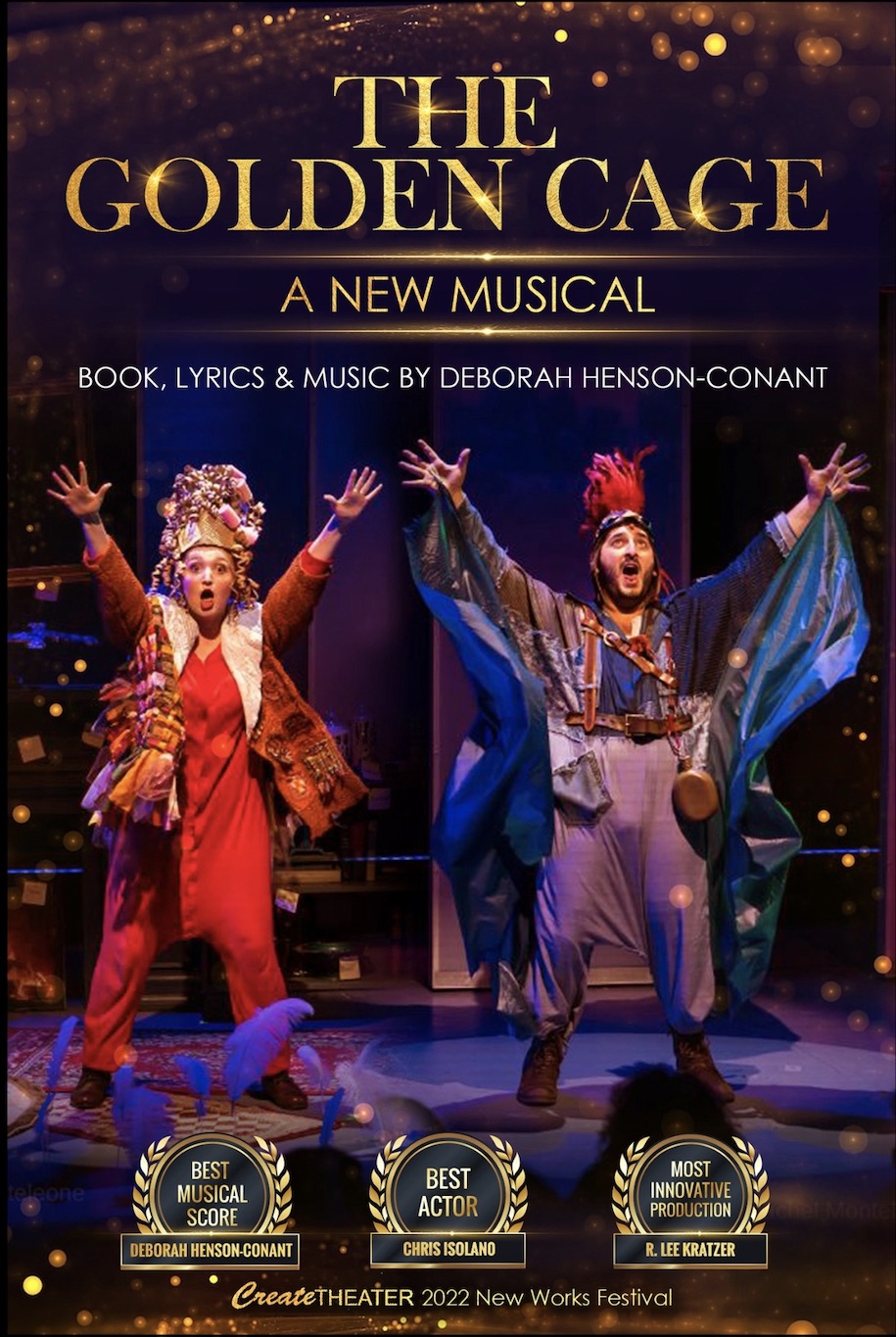

2. Since 2009 I’ve been working on a musical called “In the Wings (or “What the Hell are you doing in the Waiting Room for Heaven?) about the ultimate game show — to win a place in the heavenly choir (see AGT blog #1)

3. For the past year I’ve been in conflict with myself about a project a producer-friend wants me to do. He wants me to develop of Classic Rock harp program for orchestra, something that would take at least a year to put together, with no guarantee that it would be either artistically or financially successful His motivation is that it would be easier to sell me in that package, not that the project would deeply resonate with my own artistic values.

These all form the background of my experience with AGT which began earlier this year with an email from my agent saying “America’s Got Talent” invited you to audition” — and not just to audition, but to skip over preliminary rounds and go straight to the TV round. My first thought was, “Why would I ever want to do that?” My second thought was, “What an incredible opportunity to learn about high-pressure talent shows.”

So to my agent’s surprise I said, “Sure, what the heck?”

Once I realized it was actually happening, I started calling other friends who’d been on the show to ask for advice. They told me to expect a lot of pressure from AGT producers to “game” the show by playing familiar music (subtext: DON’T play your originals) — and a lot of hype about how good my chances were. I’m not great in situations like that so I asked this producer-friend (the one in #3 above) to run interference for me, and play the role of manager during the negotiations, which he kindly agreed to do.

I thought I was really smart to buffer myself like that, until my next phone call with him. Because suddenly HE was pressuring me to put together a list of pop-tune covers for AGT, HE was telling me I was being difficult and unreasonable, and HE was seriously questioning the validity of my insistence that I should play an original. So instead of dealing with pressure from an unknown AGT producer, I was dealing with it from someone I really like and care about — and NOT dealing with it well.

When I said I couldn’t come up with a list of five current pop tunes I could convincingly play on electric harp in a nationally -televised contest, he said, “What’s so hard about that??? It’s easy! Look, I’ll sit down with you and tell you what tunes to play. I could do it in five minutes.”

And before you fault him for this, remember he really thought he was doing the best for me: He saw what I’ve been able to do with the harp. He saw the rock energy in my playing and — I gotta love him for this — he thinks I can do anything. It’s not his fault that he loves rock, wants to see me play it, knows how to promote it, and would have LOVED for me to get National TV exposure successfully playing a well-known cover.

But I didn’t know how to hold my own in the face of his certainty about what I should be doing. I didn’t know how to articulate the fact that embodying the artistic spirit of an art form is totally different from being able to convincingly play standard repertoire. Yes, my performances are informed and inspired by the spirit of many genres and artists from Jimi Hendrix to Guiseppe Verdi, but I play very little standard repertoire from any genre, and when I do it takes years for me to make it my own.

So HE was saying, “Here’s what you have to do to win.”

I was saying, “But … but … but … but ….”

And NOBODY was saying: “Look, just be as genuinely YOU as you can be – and if you fail, fail as YOU.”

I’m embarrassed to say I didn’t say that for myself, since it was the first and most important lesson my teacher John Swackhamer taught me over 30 years ago at U.C. Berkeley (along with “If you play faster than you can, it just sounds like mush, so slow down.”)

And while it’s easy for me to see all this now, in that moment – a week before the show, when I finally knew for sure I was going to Seattle to compete, and that I’d play James Brown (and, trust me, it was waaay closer to anything I actually can do well than the other options I was given) — by then I’d lost my center:

– I didn’t want to lose the opportunity to go on the show because I knew it was a precious research opportunity for my musical.

– And I knew I was miserable, but I didn’t know whether it was because I’m unwilling to make the sacrifices that would make me a more marketable musician, or because I was being expected to do something that simply isn’t me.

The truth is that knowing “who I am” as an artist seems to be taking me a lifetime, and figuring it out sometimes means taking on roles that don’t ‘feel’ like me for a while. It’s hard for me to decipher the difference between the discomfort of molding myself into something I’m not, and the discomfort of pushing myself to greater authenticity. They’re both uncomfortable.

And since I often can’t tell which is which, the difference between getting lost and finding myself isn’t immediately clear to me a lot of the time.

I want to be clear that I really enjoyed working on James Brown, once I committed to it. I loved the process of trying to figure out how to translate a full James Brown ensemble onto solo electric harp, I loved working on my singing with producer Malik Williams, and working on the structure of the audition piece with a performer-friend who’s been on AGT several times and with whom I’d agreed on a consciously risky strategy to build the 90-second competition piece from something that was intentionally underwhelming in the first 10 seconds, to something bigger-than-life at the end. All of that was great, fun.

But when I walked onto the “America’s Got Talent” stage — the real competition was in me, churning and unarticulated — the competition between being the artist I am and trying to be a ‘marketable’ artist; between ‘doing what I uniquely do’ and embracing the opportunities of a new experience.

So there I was in the belly of the beast. My beast. And it was time for me to step out onto the stage ….

Stay tuned for “The Path to Revelation” (part 2)…

Deborah: I read this post of yours first thing this morning and it resonated so deeply with me that I felt I had to reply. I am not as eternally charitable as you are in discussing others’ musical tastes, so perhaps you won’t like what I have to say. On the other hand, perhaps it will be a revelation to you.

Like you I’m an instrumentalist (guitar) who among other things translates complex ensemble music down to a solo instrument. Unlike you I do it for a hobby rather than for a living, but nonetheless I am musically trained and I do it very seriously. The internal struggle you described during your tenure at GRP is something I resolved long ago in favor of “being myself”, but I am probably more easily able to afford that simple option than you are, since I live off the proceeds from my day job.

The question is, why do we have this struggle? I think I know the answer now after years of contemplating it. In my view, the average person, musically speaking, is like a wet match. For all the world it looks like you could strike it and get a fire out of it, but no such thing actually happens. I know this because I see it in people’s responses to my playing. Quite frankly, the vast majority of them haven’t got the faintest idea of what I’m doing or why I’m doing it. Yes they have ears to hear and voices to sing and fingers to play (you and I might reason), so interesting music must somehow appeal to them. But no … between the ears is the most important part that you and I cannot see, and in that part there is simply nothing musically to ignite. Despite appearances, I might as well be trying to evoke a reaction from a cement block.

I imagine that like me you grew up in a musically rich environment and that your upbringing involved listening to the fantastically complex instrumental music of the baroque and classical eras, or perhaps at least the jazz era. Unfortunately for people like us, the vast majority of humanity did not have such an experience. Most people have no frame of reference from which to even superficially understand what goes on in seriously interesting music. To them it is just more white noise.

By nature I am a geek who innately finds the inanimate world far more interesting than the world of humans, so it is only very lately (I am 56) that I’ve started turning my analytical skills toward understanding humans and their behaviors. Nonetheless I believe I’ve come up with some pretty good answers.

I rarely attend sporting events, but I had an opportunity somewhere back around 1990 to go to a Chicago Cubs game with a group of employees of my small company, and there, sitting in the bleachers, I had a revelation. After six innings or so of absorption in the game, I started looking around me and I realized something: the people around me weren’t really watching the game at all. Yes they had some vague notion of the score and they stood up for the “sixth inning stretch” and so forth, but mostly they were just hanging out, sunning themselves, and talking. I realized that the game, hundreds of feet away and mired in details of technical complexity and subtle nuance, was lost on them. I came to understand that the game itself was of essentially no interest to them. It didn’t really even matter to most of them which teams were on the field or perhaps even what game was being played.

So why do people go to see the Chicago Cubs or a Lady Gaga show? Is it really the game or the music? I think not. It is the arena, or the outdoors, or the social experience, or the getting out of the house, or the lousy but different food, or the white noise. It is all these things. It is the reconstruction of what would have been normal in our primeval past.

So .. imagining that I now understand the motivation behind the overall experience, my analysis turns to the question of people’s choices of what to attend. Why do they see the Chicago Cubs rather than some other team? Is it because of this team’s exceptional skill or entertainment value? Obviously not (the Cubs don’t win much). No … it is because the Cubs long ago established themselves as the default franchise for Chicago’s north side, and if you are a north-sider and you are going to see a local pro baseball game, you are going to see the Cubs. It’s that simple.

So why do people go to see Lady Gaga? Is it because of her exceptional musical skills or the profound depth of her music? I don’t think so. I have been exposed to quite a lot of today’s “pop” and my primary response is … boredom. It’s always the same old themes, the same old instrumentation, and the same old hip affectations, and Gaga is no exception. So what is it about her? Adding to the difficulty of this question is the fact that Gaga is not a default regional franchise like the Cubs … she had to “make it” in a competitive environment, so people had to find something they like in her.

The answer, I think, is that she is a spectacle. She’s a costume show. She hits on standard themes that have appealed forever to teenagers and early-20-somethings, and that’s her business. She’s a latter-day Marilyn Monroe, or Madonna, or whatever. She turns out a new album not because of some musical inspiration, I suspect, but rather because her show requires a soundtrack, and really any soundtrack will do so long as it is perceived (for the moment) as “hip”. And I suspect that, as with the baseball game, the audience isn’t really there to listen. The vast majority of the people there are there for all the same reasons that they might attend a baseball game, and in fact the show to them might as well be a baseball game.

Why do most people attend such events at all? I think it has to do with satisfying a primeval need for community, activity, and noise. Through our tribal history I imagine that our current levels of solitude were simply unattainable. People lived in an environment of constant interaction and background noise. Sitting alone in a quiet room was simply not an option. Mindlessly watching animations on a screen wasn’t, either. People were out and about, and there was a constant buzz. That’s why people today need radios and TVs constantly on in their houses … they can’t deal with the silence.

So there is a binary choice here and it is not a false dilemma: Do you want to be widely popular, or do you want to make interesting music? Looking at today’s popular acts, I’d say it is almost impossible to do both. I myself have chosen the latter, but that is an easy choice because I have no motivation to play music at all if the music is not interesting, first and foremost, to me. Recently I’ve moved from the Chicago burbs to the city of Minneapolis in the hope of meeting more like-minded people, both in my day job and in my musical efforts. But even so I understand that my audience, both professionally and musically, will always consist of a small group of people who are very much like me, and that most of them on any given night will have other things to do than come out and see me play yet again. So be it. I’d rather play to them than to a stadium full of people who are more focused on the hot dog they’re eating.

Dave — thanks so much for pouring out your story like this. I love how personal it is and I especially love this line: “Through our tribal history I imagine that our current levels of solitude were simply unattainable.”

I also love that you’ve moved (literally) to put yourself in a better place to connect with people both personally and musically. To me, that sounds like a commitment to yourself as an artist.

And what I most love is something I also saw through my AGT experience, and that I’ll write about in blogs later this week: how deep and personal the connection to artistic expression is in so many people.

On another note, I have to say I personally admire Lady Gaga – but probably because I saw her in a very stripped-down performance before she hit it big, and I was blown away by her creativity and artistic commitment. That might not be as clear in more highly-produced performances, but I’ll never forget it. I went to her show expecting to leave in five minutes and sat enraptured the entire time. For some people (like me) all the glitz of production makes it harder to see the artist — for others, apparently, it makes it easier. But as an artist and performer, I deeply admire the Lady Gaga I personally saw on stage in that stripped-down show.

I also loved what you wrote, “my audience, both professionally and musically, will always consist of a small group of people who are very much like me” – yes, I think the beauty is that, when we express ourselves artistically we make it possible for others “like us” to find us. I hadn’t ever thought of it this way until responding to your post, but just realized that through our artistic expression we can strip away the external definition of what “like us” (similar gender, race,age, language … whatever) means — and connect on what “like us” means in the deepest, least superficial and most fundamental ways. Thank you for that insight.

Deborah, Having done the NYC AGT and getting buzzed myself and after watching the program for the first time over the last few weeks I’ve come to believe that the judges have decided with the producers who goes to the next level before they step on stage. It’s all about the Cinderella , happy every after, with a $million bucks in my pocket story. I believe they assign or take on the role of good judge, bad judge before they sit in the judges chair. As past of my research for the audition I came across a movie called “American Dreamz” It is a comedy about AGT that hit’s close to home. In it the producer held all the cards and manipulated the show according to personal feelings and what they believed makes good TV. I don’t think it mattered what you played or how you played it, they needed to buzz you quick to keep from letting the audience see your talent. Our friend Fred Garbo lasted about 10 sec. also. I made it through 80 sec of my 90 sec. mostly because I didn’t stop and playing a bass drum on my back couldn’t hear the buzzers. The judges ended up flagging me down. From the beginning I felt Howie had the roll of bad judge. Later he passed me in the hall surrounded by half- a-dozen security people surrounding. Now, that seems a sad high price for fame. I think people like up the AGT losers are the real winners.

I hear what you’re saying, Rick. For me, though,, as you’ll see in the following blogs, it was ultimately hugely affirming BECAUSE of the judges. But that may be because, for me, the outward contest came to represent a deeper inner conflict I have to resolve — which is my own doubt and rejection of who I truly am as an artist.

Ultimately, I believe that it’s not the show’s or the judge’s agenda that matters — but our agenda with ourselves. They just give us a platform to play that out on. I guess for me, it’s like a Greek myth: can we hold on to ourselves as artists as we go through that challenge? Which is why I would do it again. To challenge myself to get through it maintaining my belief in my own unique artistic voice.

On the other hand … when do I get my badge for the “Buzzed Off AGT” club??

Thank you so much for sharing this experience with us! I respect you and your decision to put yourself out there more than I can say. I am surprised and somewhat comforted by the fact that you have doubts about who you are as an artist. It was watching a video of you perform the Way You Are Blues a few years ago that helped me unlock a little of my own voice as an artist. It was unlike anything I’d heard before with harp & voice and gave me a glimmer of hope that I had my own music in me. Thank you, thank you!

Thank YOU so much, Shawnmarie, for writing this! When I hear that something I did or wrote or tried or failed gives someone else courage, I feel proud. And more courageous. Thank you! I loved what you wrote.

It also made me think about the workshop I do in Maine in August, and I’m sitting here thinking … wait, if I tell her about it, is that icky, like I’m trying to sell her on this workshop … but it really sounds like she’s exactly the kind of person I love having there … so here’s the link and if you think it’s something you might want to do and you have questions, just email me at info@HipHarp.com. Also the blog that I hope to put up on Wednesday is about one of the other contestants who inspired me and made me think again about my own authentic voice. So I’ll be thinking about you when I post that one!

And here’s the link to the workshop: http://www.hipharp.com/events/celebarn-workshop.htm

Thank you so much for your wonderful comment!

Thank you for putting the workshop on my radar!